| |

| Author |

Topic Options

|

Posts:

Posts: 9914

Posted: Posted: Tue Aug 18, 2009 6:53 am

How Referees were Invented Near the start of the hockey era, games were played mostly in the winter. The games that were played in the summer soon became water polo matches, but that's another story. At first, there were not many rules. Things were very wide open then, a breakaway could take hours to bring to a stop. Soon, things like the size of the hockey 'rink' were standardized. Before standardization, rinks were as large as the lakes that Pierre and his buddies played on. This made for great exercise but quickly eroded the fan base. Rink size became the same all over Canada, players usually wore the same type of bayonets on their skates and sticks that were too curved were soon outlawed. However, players still called the shots when it came to rules about scoring and interpersonal things, such as fighting, and many players were injured in the wild and rough pre-referee days. Trappers, the guys who wore those early baseball mitts of the same name in order to 'trap' beaver and mink, sometimes resorted to an early form of camouflage which allowed them to creep up on unsuspecting animals. Camouflage, which really means 'look like an idiot', tends to make people invisible in certain surroundings. This, contrary to popular belief, does not work in malls or in schools. Anyway, at that time there were a group of trappers who were called referees. They wore black and white striped camouflage which was very useful in the birch woods of Canada. At that time there were two types of birch, white birch which you still see today, and black birch which was outlawed during Canada's brief but intense apartheid era. The word referee came from the French/Gaelic/Italian/Scotch/Hebrew word for "men who capture animals with a leather glove and who wear black and white striped shirts all the time and need glasses." The actual word sounds much like the Welsh word for flatulence and is generally unpronounceable. The referees, sturdy short men who usually were quite vain and opposed to wearing glasses, watched the games from the safety of the birch forests. Pierre and his friends often saw them standing at the edge of the forest. One day, when there was a fierce battle on the ice, several referees rushed down onto the frozen lake and took control of the game. The fighting stopped and Pierre, by now an elder statesman of hockey, asked the referees to stay and control other games. The question remains, however, as to why the referees stopped the fight in the first place. The true reason may never be known but legend states that the fight was actually started over a mink that slipped out of a referees glove and scurried down onto the ice surface. That referee, his name was Buckner as I recall, raced into the game to retrieve the mink and the players stopped fighting to help him. Hockey's early days were shrouded in the mists of time and some of the details might be a bit different from what I have written here but it makes a good story anyway, right? http://hockeyhistory411.com/referees.html

|

Posts:

Posts: 9914

Posted: Posted: Tue Aug 18, 2009 5:29 pm

The Blackhawks are one of the Original Six NHL teams, along with the Boston Bruins, Montreal Canadiens, Toronto Maple Leafs, New York Rangers and Detroit Red Wings. They have won three Stanley Cup Championships and thirteen division titles since their founding in 1926.

The Chicago Blackhawks joined the NHL in 1926 as part of the league's first wave of expansion into the United States. They were one of three American teams added that year, along with the Detroit Cougars (now the Detroit Red Wings) and New York Rangers. Most of the Hawks' original players came from the Portland Rosebuds of the Western Canada Hockey League, which had folded the previous season.

The Hawks' first season was a moderate success. They played their first game on November 17th when they played the Toronto St. Patricks at what was called the Chicago Coliseum at the time. The Blackhawks won their first game by beating the St. Patricks 4 to 1. They ended up finishing the season in 3rd place with a record of 19-22-3. The Black Hawks lost their 1927 first-round playoff series to the Boston Bruins, who had made the playoffs for the first time ever.

The 'Hawks proceeded to have the worst record in the league in 1927–28. By 1931, they reached their first Stanley Cup Final, with goal-scorer Johnny Gottselig, Cy Wentworth on defense, and Charlie Gardiner in goal, but fizzled in the final two games against the Montreal Canadiens. Chicago had another stellar season in 1932, but that did not translate into playoff success.

In 1938 the Blackhawks had a record of 14–25, and only barely made the playoffs. They stunned the Canadiens and New York Americans on overtime goals in the deciding games of both semifinal series, advancing to the Cup Final against the Toronto Maple Leafs. Blackhawks goalie Mike Karakas was injured and could not play, forcing a desperate Chicago team to pull minor-leaguer Alfie Moore out of a Toronto bar and onto the ice. Moore played one game and won it, but repeating the plan with another player failed as the Hawks lost the game. However, for Games 3 and 4, Karakas was fitted with a special skate to protect his injured toe, and won both games. It was too late for Toronto, as the Hawks won their second championship. To this day, the 1938 Blackhawks possess the poorest regular-season record of any Stanley Cup champion.

|

Posted: Posted: Tue Nov 24, 2009 12:17 pm

Conn Smythe Constantine Falkland Cary Smythe MC (February 1, 1895 – November 18, 1980) was a Canadian businessman, soldier and sportsman in ice hockey and horse racing. He is best known as the principal owner of the Toronto Maple Leafs of the National Hockey League (NHL) from 1927 to 1961 and as the builder of Maple Leaf Gardens. As owner of the Leafs during numerous championship years, his name appears on the Stanley Cup eleven times: 1932, 1942, 1945, 1947, 1948, 1949, 1951, 1962, 1963, 1964, and 1966. Smythe is also known for having served in both World Wars, organizing his own Battery in World War II. The horses of Smythe's racing stable won the Queen's Plate twice among 145 stakes races wins during his lifetime. Smythe started and ran a successful sand and gravel business. Smythe was a big supporter of the Ontario Society for Crippled Children and the Variety Club and founded the Conn Smythe Foundation philanthropic organization. Tim Horton Myles Gilbert "Tim" Horton (January 12, 1930 – February 21, 1974) was a Canadian professional hockey defenceman. He played in 24 seasons in the National Hockey League for the Toronto Maple Leafs, New York Rangers, Pittsburgh Penguins, and Buffalo Sabres. He was also a businessman and the co-founder of Tim Hortons, now Canada's largest restaurant chain. He died in an automobile crash in St. Catharines, Ontario, in 1974 at the age of 44. Not long after Horton's death, Ron Joyce offered Lori Horton (Tim's widow) $1 million for her shares in the chain, which included 40 stores by that time. Once she accepted his offer, Joyce became the sole owner. Years later, Mrs. Horton decided that the deal between her and Joyce had not been fair and took the matter to court. Mrs. Horton lost the lawsuit in 1993, and an appeal was declined in 1995. Lori died in 2000.[5] Tim and Lori left four daughters, Jeri-Lyn (Horton-Joyce), Traci (Simone), Kim and Kelly. Jeri-Lyn married Ron Joyce's son Ron Joyce Jr. and owns a store in Ontario.

|

Posts:

Posts: 9914

Posted: Posted: Sat Mar 20, 2010 6:40 am

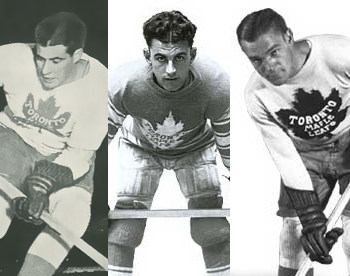

The Kid Line was a NHL line for the Toronto Maple Leafs in the 1930s. It included Charlie Conacher, Harvey "Busher" Jackson and Joe Primeau. When they first came together as a line, Primeau was the oldest at 23 years old, while Jackson and Conacher were both 18. All three players are members of the Hockey Hall of Fame. Maple Leafs coach Conn Smythe, put the line together, and it helped the Maple Leafs to a Stanley Cup championship in 1932, and lead the Leafs to four Stanley Cup finals appearances over the next six years.

|

Posts:

Posts: 9914

Posted: Posted: Sat Mar 20, 2010 6:44 am

The Kraut Line was the term used to describe a trio of hockey players who played on the same NHL forward line who were members of the Boston Bruins hockey team: center Milt Schmidt, left wing Woody Dumart, and right winger Bobby Bauer. The name was devised by Albert Leduc, a player from the Montreal Canadiens between 1925 and 1933, and references the German descent of all three players, all of whom grew up in Kitchener, Ontario. The three were famously attached and lived together in a single room in Brookline, Massachusetts. This line was so accomplished that in the 1939–1940 season, the trio was 1–2–3 in NHL scoring. Center Milt Schmidt lead the league in scoring with 22 goals and 30 assists; left wing Woody Dumart was second in the league with 22 goals and 21 assists; and third in scoring was right wing Bobby Bauer with 17 goals and 26 assists. While the line was intact, the Boston Bruins would win the Stanley Cup championship in the 1938–1939 and 1940–1941 seasons.

|

Posts:

Posts: 9914

Posted: Posted: Sat Mar 20, 2010 7:07 am

Many Hockey players replenish lost fluids after the game. Alfie Moore was in a pub drinking just before the biggest game of his life. The Black Hawks were in Toronto with a big playoff game and no goalie. Mike Karakas, Chicago's starting goalie, was hurt. Conn Smythye wouldn't allow them to use Ranger Goalie Dave Kerr, a Toronto native, so Chicago coach Bill Stewart went to the only other goalie he knew in Toronto. At a team meeting he asked if anyone knew where Alfie could be found, someone dryly suggested they start checking the city bars, a search party shortly found him at a nearby tavern. He's been there quite awhile so it took quite a few coffees to "rinse him free of the suds". Stewart asked his players to take it easy on him in warm up so as not to get him hurt. It was said that Stewart eyed Alfie with evil regret all through the warm up and it seemed to be with good reason as Alfie fanned on his first shot giving Toronto the lead. After Alfie saw the disappointment on the faces of his new team mates, his resolve was strengthened considerably. After that, he was invincible stopping every Leaf attack leading Chicago to a 3-1 victory. As he was leaving the game the Black Hawk management asked him what he wanted for the one night of work he said, " Would $150.00 be reasonable?". The Hawks paid him $300.00 and put his name on the Stanley Cup.

|

Posts:

Posts: 9914

Posted: Posted: Mon Apr 11, 2011 5:00 pm

If not the best goalie of all time, Jacques Plante was certainly the most important - the man who introduced the art of modern goaltending to the NHL and whose influence is seen every night a game is played. "Jake the Snake" was born in Shawinigan Falls, Quebec, and from the time he started playing, his destiny was to play for the Montreal Canadiens. After a usual four-year apprenticeship with the Montreal Royals in Quebec senior hockey and two years with the Buffalo Bisons, Plante quickly emerged as Montreal's goalie of the future. He played a few games for the Habs in 1952-53 and 1953-54, and in his first full season began an incredible run of five consecutive Stanley Cup wins and five consecutive Vezina Trophy wins, records that have yet to be equaled. Throughout his career he was plagued with recurring asthma and after missing 13 games due to a sinusitis operation, Plante began wearing a mask in practices in 1956. Coach Toe Blake endorsed the move cautiously because it kept his goalie healthy and happy, but he warned Plante that a mask wasn't permitted during games. However, during a Montreal versus New York game the night of November 2, 1959, Plante was hit in the face by a shot. He went off to the dressing room for stitches and when he returned he was wearing a mask. Blake was livid, but he had no other goalie to call upon and Plante refused to return to the goal unless he kept the mask. Blake agreed on condition that Plante discard the mask when the cut had healed. In the ensuing days Plante refused, and as the team continued to win, Blake became less obstinate. The Montreal record stretched into an 18-game unbeaten streak with Plante protected and the mask was in the NHL for good. Plante was a pioneer of the style of play for goaltenders as well. While there had been other goalies before him who periodically came out of their crease to play the puck, he was the first to skate in behind the net to stop the puck for his defensemen. He also was the first to raise his arm on an icing call to let his defensemen know what was happening on the ice, and he perfected a stand-up style of goaltending that emphasized positional play, cutting down the angles and staying square to the shooter. His book, The Art of Goaltending, was the first of its kind and solidified his place in the game as not just a great stopper but a man who truly understood hockey and wanted to have an influence on how the game would be played in the future. Plante retired in 1965 after playing two seasons with the Rangers, but he was lured out of retirement by the St. Louis Blues and the prospects of sharing the goaltending with the great Glenn Hall for the expansion team. Together they took the Blues to two Stanley Cup finals, and in 1969 Plante shared the Vezina Trophy with Hall at the ripe old age of 40. He also played with Toronto and Boston and played for one final season with the Edmonton Oilers in the WHA before becoming a scout and goalie coach in St. Louis. In 1962 he was the last goalie to win the Hart Trophy before Dominik Hasek in 1997, and he ranks among the leaders in games played and shutouts. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1978.

|

Posts:

Posts: 9914

Posted: Posted: Mon Apr 11, 2011 5:11 pm

Although Johnny Bower's nickname was "the China Wall," it might better have been "Perseverance," for although he had a Hall of Fame career in the NHL, it certainly didn't adhere to the traditional notion of what a life in pro hockey should be about.

Bower grew up in rural Saskatchewan, the only boy in a family of nine children. He was dirt poor and never had the proper equipment. He made his goalie pads from an old mattress; he made pucks, "cow pies," from horse manure; his dad would look for suitably crooked tree branches to shave into sticks; a friend gave him his first pair of skates because his father couldn't afford to buy him a pair; and still he refined his game to become one of the best goalies of all time. In 1940, when he was 15 years old, Bower lied about his age for the first time, though not the last, in order to enlist in the army. He was sent to a training camp in British Columbia and was eventually called up by the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders and shipped to England. Four years later, he became sick during his service and was discharged in 1944, at which time he resumed his junior career with Prince Albert.

From there he began a career in the American Hockey League, which is where most goalies start out. The difference was that Bower played for Providence and Cleveland for an incredible eight full seasons before playing a single NHL game. In 1953-54, he played the entire season for the Rangers, but then spent most of the next four seasons right back in the minors, having lost the starting job in New York to Gump Worsley. During his 14 years in the minors, he won the Les Cunningham Award as the AHL's best player three times and the Hap Holmes Award for top goaltender another three times.

Bower's big break came in the summer of 1958 when the Leafs, for whatever reason, claimed him from Cleveland at the Intra-League Draft. Bower was at first reluctant to join the Leafs, even though they had finished in last place the previous season, telling them he could be of no help to the team. It was only after being threatened with suspension that he showed up for training camp that fall, and within days he had established himself as the team's number one goalie at age 34. He was to play a total of 12 years with the Leafs.

Bower, like his other five Original Six brethren, became famous for his fearless play. Maskless, he never shied away from an attacking player and in fact patented the most dangerous move a goalie can make - the poke-check. Diving head-first into the skates of an attacking player at full speed, Bower would routinely flick the puck off that player's stick and out of harm's way. One time he got a skate in his cheek, knocking a tooth out through his cheek. He suffered innumerable cuts to his mouth and lips and lost virtually every tooth in his mouth from sticks and pucks, but almost to his last game, he never wore a mask. And under the confident eye of coach Punch Imlach, Bower got better and better. He led the Leafs into the playoffs his first season with a miracle comeback ending to the schedule, and then lost two finals in a row before winning three consecutive Stanley Cup championships - 1962 to 1964.

At this time, Bower's career seemed precarious. Imlach noticed that Bower was having trouble with long shots and ordered his keeper to undergo an eye exam. Sure enough, he was short-sighted. But Bower refused to retire and kept right on going, teaming with Terry Sawchuk to win the memorable 1967 Cup with Toronto's Over-the-Hill Gang of players, led by the 43-year-old Bower himself.

After he retired in 1970 as the oldest goalie ever to play in the NHL, Bower remained with the Leafs for many years as a scout and then goalie coach, putting the pads on and helping Leaf goalies in practice. At one injury-riddled time during the 1979-1980 season, he came within a whisker, at age 56, of dressing as the team's backup. A member of the Hockey Hall of Fame, Bower is one of only a select few to have his number honored by the Leafs.

|

Posts:

Posts: 9914

Posted: Posted: Sat Apr 30, 2011 1:11 pm

Arguably the greatest hockey game ever played......

As I was too young to remember the Summit Series, I do remember watching this game and how much excitement and trepidation it cause in all the adults that came over to my Mom and Dads to watch the game and bring in the new year.

|

Posted: Posted: Tue Oct 18, 2011 4:30 am

QBC QBC:  Find cool stuff from hockey's history! Really a great stuff with cool pics and captions... Totally, I am impressed

|

Posts:

Posts: 9914

Posted: Posted: Thu Nov 20, 2014 7:07 pm

$1: Nova Scotia has a long-standing claim as the birthplace of hockey, but it also holds a lesser-known distinction from the national game’s formative years. In the 1800s and into the 20th century, hockey, like many other parts of society, was segregated. But that didn’t stop African-Nova Scotians from playing the game. For more than 30 years starting in 1894, the Colored Hockey League of the Maritimes featured teams such as the Dartmouth Jubilees, Truro Sheiks and Africville Seasides. It is believed to have been the only all-black hockey league of that time. “It isn’t all that well-known,” said Irvine Carvery, whose great-uncles played for the Seasides. “It’s a significant part of our history.” Carvery, president of the Africville Genealogy Society, said the league, which included teams in Prince Edward Island, was an important part of the community and contributor to the modern game. “Most of the teams were organized around people who were very active in the church, so it was more than just a hockey team; it was a community development team,” said Carvery. “Even though it was a rough-and-tumble sport, believe it or not, the values of the church were still enshrined in the league.” Carvery said the league was known for offering exciting hockey played in packed arenas. Unlike the white man’s game, slapshots were allowed and goaltenders could drop to the ice to stop the puck. Both rules were later adopted in other leagues. The little-known chapter in the province’s, and country’s, hockey history is the also the subject of a book — Black Ice: The Lost History of the Colored Hockey League of the Maritimes, 1895–1925, co-authored by George and Darril Fosty. Carvery and George Fosty are among the panellists who will be talking about the league at this weekend’s hockey conference at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax. The gathering of scholars and academics from North America, Europe and New Zealand will take a wide-ranging look at hockey as an aspect of society and its impact on the community. It is the sixth in a series of conferences that started in 2001. Chairman Colin Howell, academic director at the Centre for the Study of Sport and Health at Saint Mary’s, said he organized the first one in the run-up to Halifax hosting the world junior hockey championship. The diverse topics at this year’s event range from hockey moms and hockey’s “bad boys” to the legal liability of hockey officials and public attitudes about Russion defectors to the NHL. Jonathan Fullard, a master’s student at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ont., is scheduled to discuss his thesis, titled Investigating Player Salaries and Performance in the National Hockey League. Part of his study looked at how goalie performance measures related to their salaries, and he said the results were unexpected. “I really thought save percentage would be easily highly predictive of salary,” he said. “I used eight statistics, and out of all the statistics I used, only games played was significant. So it’s basically if the goalie plays more, the goalie has a higher salary, which surprised me.” Fullard, 23, also investigated whether a team’s salary structure — widely dispersed with a few players making big money, or compressed with salaries closer to an average — in the salary-cap era was a way to predict how well the teams would do. His study indicated that paying for stars did seem to pay off for teams, but there are so many other factors that affect team performance that his results may not have much application in the real world. Fullard, a native of Ajax, Ont., said he is hoping to parlay his love of hockey and Moneyball-esque interest in analytics into a career in the NHL or working with elite athletes in other sports. He said he is looking forward to talking about the study at the conference and hearing ideas about what he may have done differently. “Just a fruitful discussion on hockey, basically. I mean, who wouldn’t look forward to that?” The conference runs from today to Saturday. Information is available at http://www.hockeyconference.ca.

|

Posts:

Posts: 9914

Posted: Posted: Thu Nov 20, 2014 7:13 pm

|

Posts:

Posts: 9914

Posted: Posted: Sat Dec 27, 2014 10:00 am

Gore Bay hockey team of Manitoulin Island, Ontario, 1921 Gore Bay hockey team of Manitoulin Island, Ontario, 1921$1: Women and girls have taken to ice hockey in unprecedented numbers since the early 1990s. Female leagues and co-ed programs have changed the face of the game in many communities, and elite women's hockey has emerged as an intercollegiate and Olympic sport.

But women's hockey is hardly a new game. In fact, women and girls have been forechecking, backchecking and crashing the crease for over a century.

The Canadian Hockey Association says the first recorded women's hockey game took place in 1892 in Barrie, Ontario. "Total Hockey," the official encyclopaedia of the NHL, places the first game in Ottawa, where the Government House team defeated the Rideau ladies team in 1889. By the turn of the century, women's hockey teams were playing across Canada. Photos suggest that the standard uniform included long wool skirts, turtleneck sweaters, hats and gloves.

This first era of women's hockey peaked in the 1920s and 1930s, with teams, leagues and tournaments in almost every region of Canada and a few areas of the United States. Some of the best Canadian teams met annually in an East-West tournament to declare a national champion. The Preston (Ontario) Rivulettes became the first dynasty of women's hockey, dominating the game throughout the 1930s.

The organized women's game declined after World War Two and throughout the 1950s and 1960s was regarded as little more than a curiosity. Hockey was assumed to be the preserve of men and boys, an attitude confirmed in 1956 when the Ontario Supreme Court ruled against Abby Hoffman, a nine-year-old girl who challenged the "boys only" policy in minor hockey. Hoffman had already played most of the season with a boy's team, disguising her sex by dressing at home and wearing her hair short.

A revival began in the 1960s. Most girls attempting to join boys teams were still rejected. But women's hockey slowly gained ice time, and as the new generation of players grew up they demanded a chance to play at colleges and universities. Canadian intercollegiate women's hockey began in the 1980s and the NCAA recognized the game in 1993.

An international breakthrough came in 1990, when eight countries contested the first Women's World Ice Hockey Championship. Participation grew exponentially in the decade that followed. Women's hockey made its Olympic debut at the 1998 Games in Japan. In 2002 the Mission Bettys of California became the first all-girls team to enter the Quebec International Pee Wee Tournament, one of the world's largest youth competitions.

Today the number of female hockey teams and leagues is at an all-time high. Mixed gender teams are also more common, especially in youth hockey. The game remains a male-dominated culture, but girls and women face much less of the obstruction and prejudice that frustrated their predecessors.

A few women, including goaltenders Manon Rheaume and Erin Whitten, have played on men's professional teams at the minor league level. In 2003, Hayley Wickenheiser joined Salamat of the Finnish Second Division and became the first woman to record a point in men's professional hockey, finishing the regular season with one goal and three assists in 12 games.

Although applauded by most fans, Wickenheiser's move inspired debate about women's and men's hockey. Some say elite women's hockey will never grow if the best players migrate to men's leagues. The president of the International Ice Hockey Federation, Rene Fasel, has declared his opposition to mixed teams.

"I don't understand why anyone should feel threatened," said Teemu Selanne, the NHL star who is part owner of the Salamat team. "This is the best women's hockey player we're talking about. It's not as if five or six women are going to start appearing on every men's team."

There may be more Wickenheisers to come, but for most women the future is in the women's game. The rivalry between Canada and the United States is the marquee attraction. Canada's 3-2 win over the U.S. in the 2002 Olympic gold medal game drew a television audience of millions on both sides of the border.

The National Women's Hockey League began in 2000, giving top players on both sides of the border a chance to play outside the college or international systems. The Western Women's Hockey League was established in 2004.

Canada and the United States remain the dominant countries, and other nations must close the gap if women's hockey is to thrive at the international level. Sweden took a huge step forward in this regard by winning the silver medal at the 2006 Olympics, upsetting the USA in a landmark playoff game. The Swedish goaltender, Kim Martin, emerged as the new face of women's hockey with a standout performance.

Girl's and women's hockey is one of the fastest growing games in the world, suggesting that future fans and players will likely view this era as the infancy of a popular and widespread sport.

Earliest known photograph of women playing hockey, taken at Rideau Hall, Ottawa, circa 1890. Isobel Stanley, Lord Stanley's daughter, is wearing white Earliest known photograph of women playing hockey, taken at Rideau Hall, Ottawa, circa 1890. Isobel Stanley, Lord Stanley's daughter, is wearing white

|

Posts:

Posts: 9914

Posted: Posted: Sat Dec 27, 2014 3:38 pm

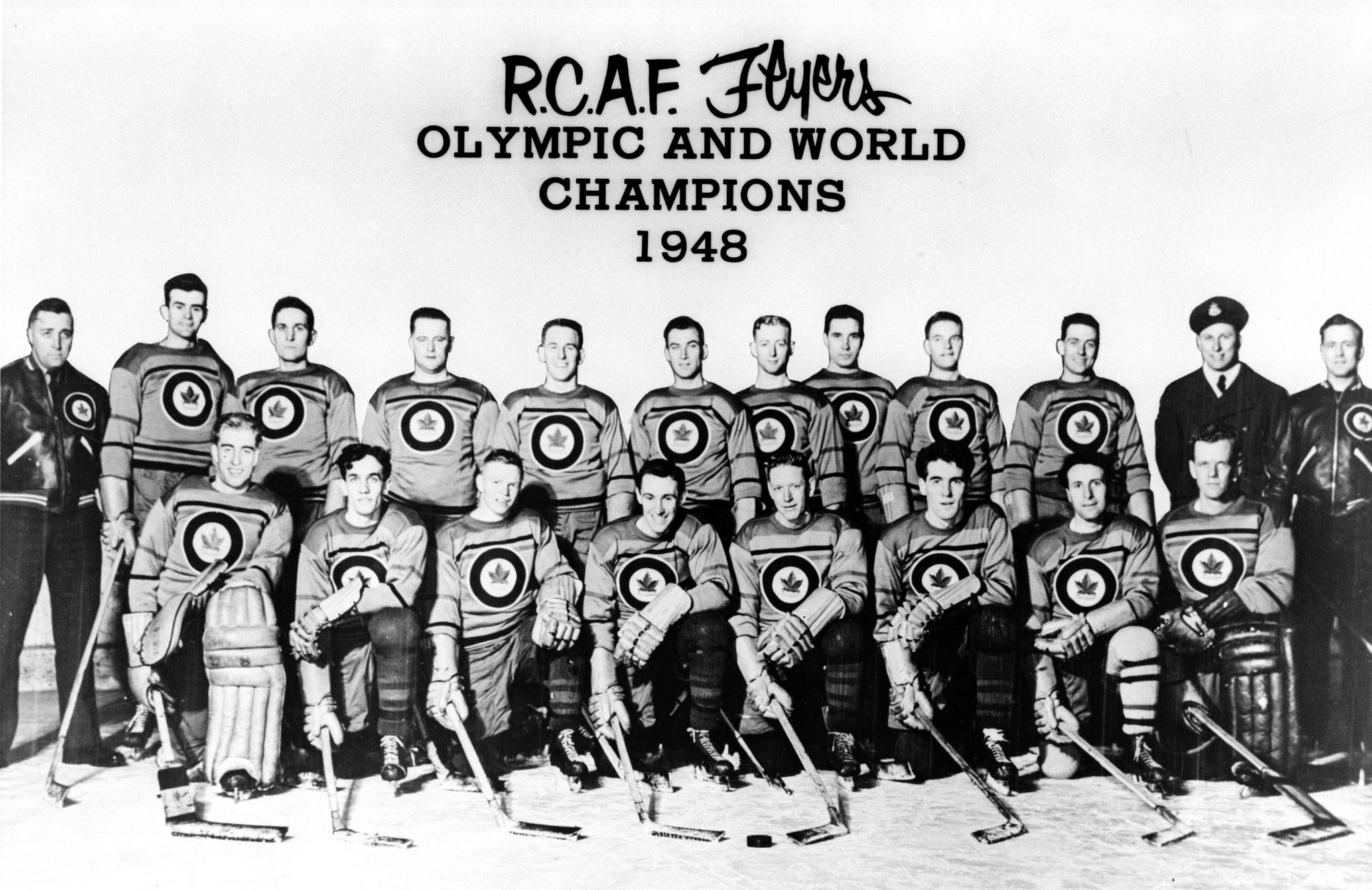

$1: Because of the Second World War, there had been a 12-year break between Winter Olympic competitions. The Games at St. Moritz marked Canada's return to international competition for the first time since before the War.

The problems that had plagued the Americans at the 1947 World Championships produced grave complications in 1948, as two American teams arrived in Switzerland. One team was sent by the Amateur Hockey Association of the United States and was supported by the IIHF, while the other was sent by the Amateur Athletic Union, which had represented the United States at all previous Winter Games and now used its old connections to gain support from the International Olympic Committee.

Both American teams appeared on the ice for the opening ceremonies and police assistance was required to restore order. The IOC decided to disqualify both American teams, but passions later calmed and the AAU team left for home. This allowed the IOC to withdraw its suspension and reinstate the AHAUS team. In the end, the United States entry was "outlawed" by the IOC and was not counted in the final Olympic hockey standings (though it remained in the World Championships).

Problems also plagued the Olympic tournament on the ice, where warm weather played havoc with the schedule and made it necessary to begin some games at 7 a.m. For the first time in history, a team went through an Olympic hockey tournament undefeated and failed to win the gold medal. The victim of the single round-robin format was Czechoslovakia, which played to a scoreless tie with gold-medalist Canada, represented by the Royal Canadian Air Force Flyers. The Czechoslovaks had to settle for a silver because the Canadians had a better goals for and against differential of plus-64, compared to their plus-62.

In essence, the gold medal was decided when Canada trounced the eventual fourth-place United States team 12-3 and Czechoslovakia struggled to beat the Americans 4-3. The star of the Canadian team was Wally Halder, who recorded 29 points on 21 goals and eight assists. Halder, a civilian who had been added to the team just 10 days before the team sailed for Europe, scored six times in what turned out to be the all-important victory over the U.S.

For the first time in a championship in which Canada competed, the winner was not decided until the final game. The results proved that Czechoslovakia's World Championship in 1947 could not solely be attributed to Canada's absence. It was generally agreed that the Czechoslovak team was comparable to Canada's and boasted a much stronger offense. Czechoslovakia's captain Vladimir Zabrodsky, who scored 27 goals in the tournament, was recognized as the Olympics' best forward.

The bronze medal went to Switzerland, just as it had 20 years earlier when the Winter Olympics had also been staged in St. Moritz.

|

Posts:

Posts: 9914

Posted: Posted: Mon Mar 02, 2015 10:02 pm

$1: In 1978, as a guest of the Czechoslovakian Hockey Federation, Mike Buckna was honoured as the “Father of Czechoslovakian Hockey” in recognition of his contributions to the sport of hockey in general and to the Czech game in particular.

Buckna joined the Trail Smoke Eaters in 1932 while still in the juniors, and played with the team to the first of their six BC championship wins (1931-33, 1940-41, 1949).

In 1935, he was hired to coach Czechoslovakia’s national hockey team. Buckna reorganized the country’s entire hockey system, pioneering hockey clinics, coaching junior and senior teams, and introducing minor hockey.

He served as playing coach of the Czech National Team, which won two European hockey titles in 1938 and 1939. In 1939, his National Team ironically lost to his hometown Trail Smoke Eaters 2-1 in the world championships.

Returning to Trail during WWII, Buckna played for the Smoke Eaters’ 1940 and 1941 BC championship teams.

In 1946, he returned to Czechoslovakia to coach the national team, leading them to the country’s first ever world hockey championship in 1947. This marked the first time a European team had won the world championship.

The Czech national team won a third European title in 1948. Buckna predicted that the NHL would be coming to Europe for players and at the time he was laughed at. Decades later, he would be proved correct.

Back in Trail, as player/coach for the Smoke Eaters, Buckna won the 1949 BC championship. In 1956, he turned down a coaching position with the Canadian national team to coach the newly formed Rossland Warriors.

http://www.bcsportshalloffame.com/inductees/inductees/bio?id=192&type=person

|

|

Page 3 of 4

|

[ 46 posts ] |

Who is online |

Users browsing this forum: No registered users and 1 guest |

|

|